Hiring Sucks! Reflections & The First Step (of 5)

“There’s only two guarantees in life, death and taxes,” I’d like to add a third, that hiring sucks. It’s a universal truth, and if you’re applying for jobs it’s even worse. It’s a fascinating reflection of how we have evolved and interact with each other as social animals. This post is the first of a series of 5 that explores a few frameworks I’ve used to help navigate hiring.

I’d like to premise this by saying I’ve made a bunch of hiring mistakes, and I have no doubt that I’ll make some more. But I’ve also found amazing talent and have been able to groom colleagues into leaders I’m lucky to call friends today.

The journey of starting a business starts with building a product or service, and doing most of the work yourself before convincing others to join you in serving your customers. This process is a beautiful but difficult exercise. Naturally, anything that involves random humans coming together is complex.

Then there comes a time in every business (the fortunate ones at least) when the customer demands exceed the capacity of the team doing the work, and that’s when growth slows or quality starts to diminish. For operators with high agency, the immediate response is to work harder. Spend more time at the office, sleep fewer hours, push longer and try to increase productivity. A special few would take a step back and assess what levers they can push / pull to gain leverage (Naval speaks about leverage at length, and it’s a thought worth exploring if you haven’t already).

We gain leverage by improving one (or all) of three variables in a simple equation: What you do [+] Who you do it with [+] How you do it → improving any of the three levers is more impactful than attempting to change how “hard” you work.

What you do should be answered by the customer, observing, listening to, designing for and then iterating with the earned insights.

Who you do it with is 100% in your control.

How you do it, is your modus operandi and will always change over time.

Our role as operators is to identify what needs to be solved (first), and how to solve it. But we don’t always need our team members to do both. A good team member would know how to get a job done. A great team leader would know what problems to prioritize. A star would know how to do both.

Let’s pause there and address the elephant in the room. Hiring, regardless of experience, is daunting, intimidating, filled with posturing, and ends with making big decisions from a few brief meetings. It takes a candidate approximately 27 applications to land one job interview (source). On average, managers conduct 3 interviews for mid-level roles and 5 interviews for leadership roles (source). And even if we find the perfect candidate, about 30% of new hires resign in the first three months of employment (source). The process is highly inefficient, and I can’t wait for the day that someone cracks the code.

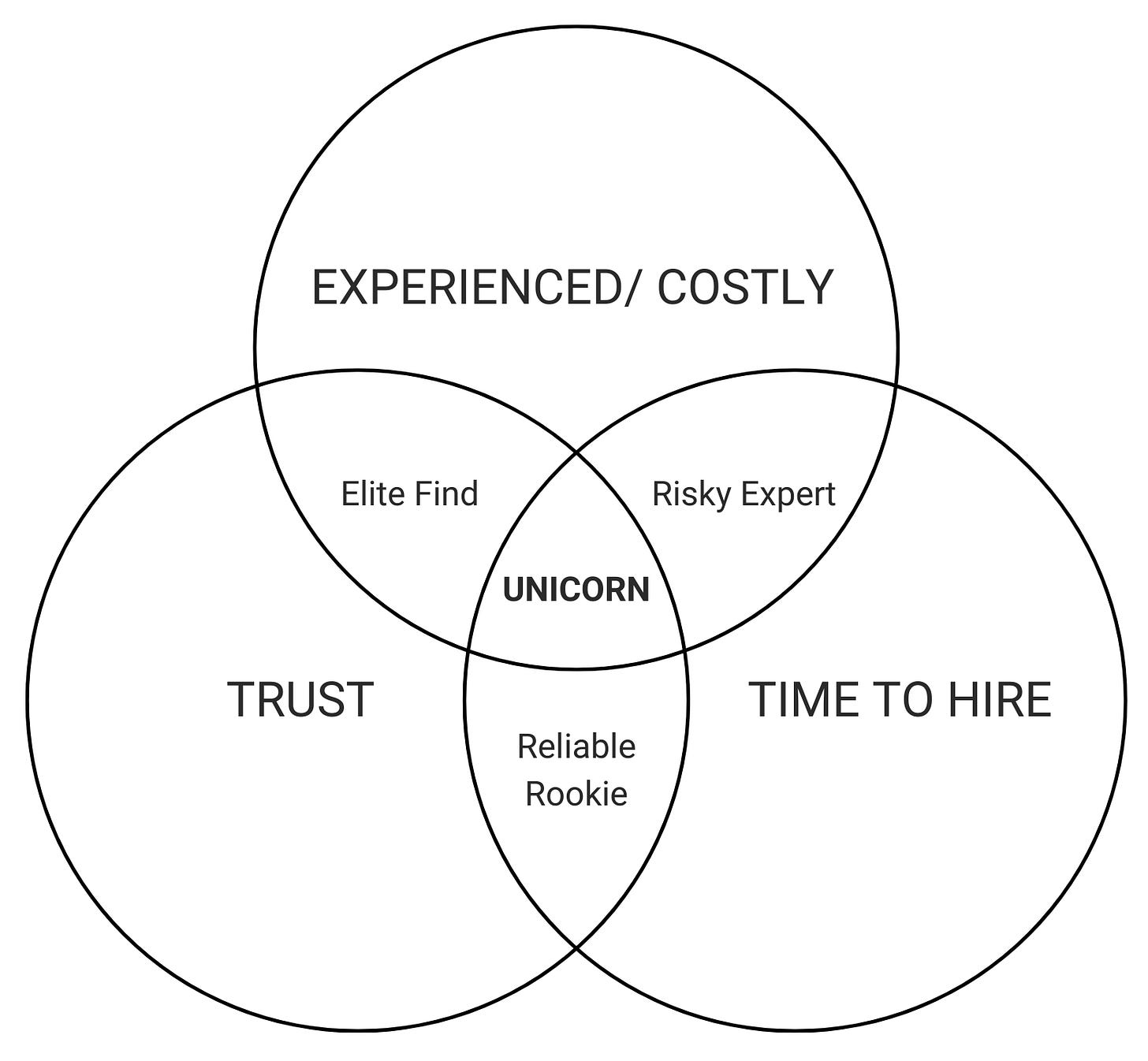

My primary reflection on hiring is that it’s a simple trade between three variables where you can only optimize for two at a given time. Today, before I start any hiring process, I answer three simple questions to identify the type of candidate I’m looking for:

How much time do I have to fill the role?

What’s my budget, and what expertise do I need to onboard?

How important is trust for this role? *

* I’ll share more about my journey with trust, and the trust equation in hiring. TL;DR it’s simply how well we can assess the reliability of the person’s ability to perform the job.

We end up with four types of candidates. Unicorns don’t exist (and if you come across one, you should partner with them, not hire them) so we’re left off with three personas. Different situations require different personas. There’s the general rule of build with generalists and scale with specialists, but I think that’s a simple view of approaching a complex task like scaling a company. Anecdotally, my experience sways towards Reliable Rookies or Elite Finds, that probably highlights my preference to over index on trust and trust building in general (which we’ll get to in the coming posts).

Here are a few actionable scenarios from the diagram above:

❓ In a high performance culture where you can only afford to have A players on the team, hiring only A players will slow you down because of the time it takes to find them.

Would you risk reducing your growth rate to hire A players or trade off the caliber of the team in favor of hiring fast to maintain a growth rate?

In the coming posts, we’ll dig deeper into the four steps I use to find “who you do it with” from formula (What you do [+] Who you do it with [+] How you do it):

Pre-hiring and pre-interview

The interview process & culture fits

Reference interviews and negotiating the offer

Onboarding and setting up for success

Thanks for reading this far. If you’re an operator that’s had a success in hiring, feel free to share any useful hacks you’ve used or picked up below! I look forward to reading them.